Read Time: 7 mins

The desert whipped at his face and clawed at his eyes, but he dared not blink. His hand hovered near his holster. His eyes were wide, raptor-like, waiting for the tell. A shift of weight, perhaps, or a twitch in the trigger finger. Somewhere nearby, a rusty hinge squeaks and a saloon door bangs shut. You see, in this world, there are two kinds of people – those who read this and imagine the haunting melody of Ennio Morricone. And those who don’t, but would recognise it if they heard it.

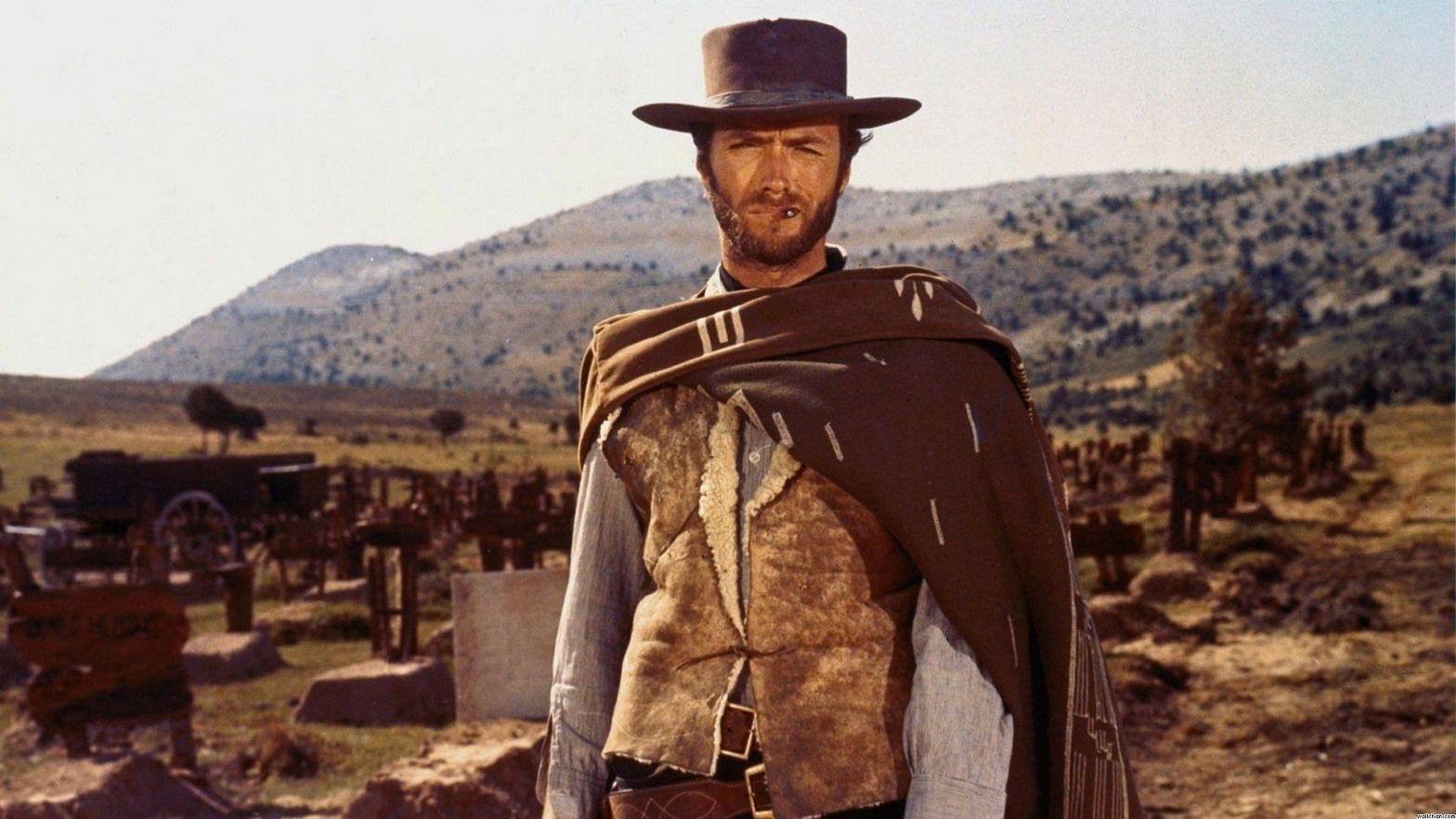

The western genre was wildly popular throughout the 20th century. They were Stalin’s favourite (but don’t let that put you off). In almost all of them, the story is the same. A rugged, morally ambiguous hero brings their own principled justice into the lawless Badlands of the deep west.

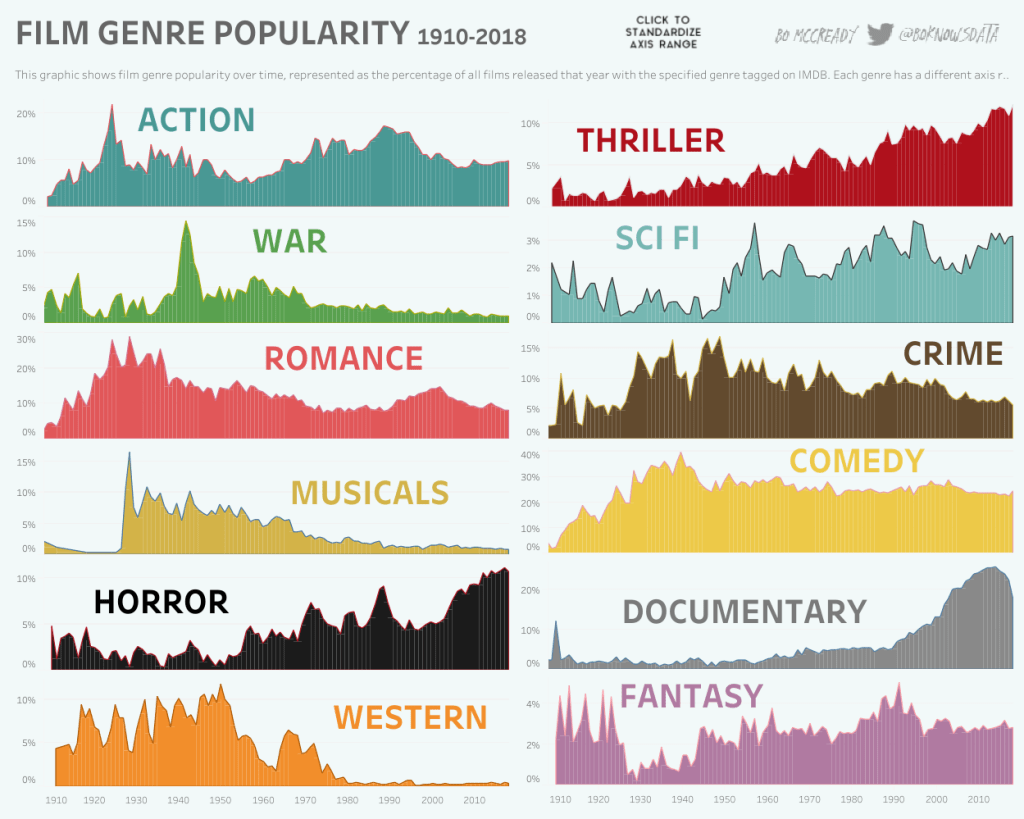

As of 2025, the popularity of Westerns is at an all-time low. They have given way to CGI science fiction and beefy superheroes. The genre still exists, but in fusion form. If you want a modern western, try something like No Country For Old Men, The Revenant, or Justified – westerns all, with dollops of modernity. Even Mr Bates vs The Post Office has a Western vibe.

But looking at IMDB, the days of a gun-tottin’ cowboy are diminished.

They were called Westerns because they all took place in the Wild West, the frontier out beyond the populated East Coast of the United States; a land of natives where seams of pure gold criss-crossed the arid plains. It was considered wild because civilisation had not yet kissed that part of America (some places are still waiting). It was lawless. Any order was imposed through the threat or execution of violence. And that makes them interesting.

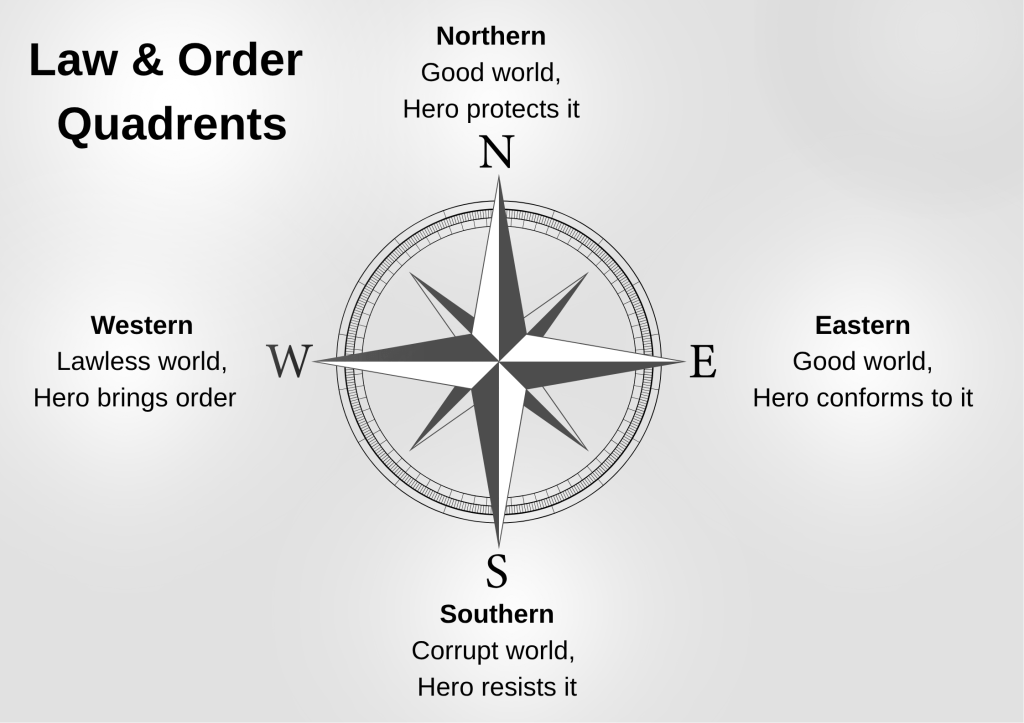

Journalist Malcolm Gladwell believes that the Western film is much more than simply a direction of travel. It forms an archetype, one that has 3 siblings – The Eastern, The Northern, and The Southern. These four categories all tell stories in relation to power, but the stories and the lessons are very different for each.

The Eastern

Consider the cowboy. Picture Clint Eastwood in his prime. Steely gaze. Cool as hell. Our protagonist in a Western is confident. They are principled. In short, they bring a form of order into a disorderly world. In the Eastern genre, our protagonist is the polar opposite. We’re introduced to a naïve, lost soul. They’re an outsider, a misfit living in a world that is good and wholesome, if only they could overcome themselves and realise their potential.

These stories are usually transformational or coming-of-age. Think Good Will Hunting – Matt Damon is a lost, angry, wild genius who meets someone worldly and wise, who has been there, done that, and painted the picture. Slowly, through a series of beautiful monologues, British sass and a strange reference to apples, he conforms, integrates and realises his potential.

Good Will Hunting is a great movie, but in reality, you could take anything Disney has made over the last 100 years and it fits this mould. If you want to “Go The Distance” or if you “Just Can’t Wait To Be King”, then you’re probably in an Eastern.

The Northern

For a Northern film, the existing power structure needs to be good here too. The difference between an Eastern and a Northern is that our Protagonist knows it’s good, and so their primary role is to protect and preserve it. They are confident and self-aware. Selfless in many cases. They are not basement-dwelling depressives who need to get a job. The Northern hero guards and maintains the status quo against those who would seek to poison and destroy it.

Now, that’s not to say there’s not a little room for personal growth. The better stories have a bit of that in them. But usually, the protagonist is a good person (occasionally tortured), who does one thing – kill the bad guy.

Enter Marvel – the money-making superhero rollercoaster that churns out so many cash cows it’s a surprise they’ve not tried to sponsor the Taj Mahal. Every single film or series follows this trope. In fact, most of the big franchises, from Lord of the Rings to Star Wars, are Northern stories through and through. In each case, the job of the hero is to protect obviously benevolent systems of power from evil. And, if there’s time to hit the gym in between showdowns, why not?

The Southern

Here’s where we flip the script. Our protagonist in a Southern may be self-aware, they might not be. But in every case, they are fighting against an oppressive, broken, tyrannical system of power. These are where dystopian fiction sits. Our protagonist is Winston from 1984, Ofred from The Handmaid’s Tale, V from V for Vendetta, Guy in Fahrenheit 451, and Bernard in Brave New World.

The Southern is the most complex of all the points on this compass. Revolution is their only salvation. They need to overthrow the system in which they operate. But at what cost? Southern protagonists often lose themselves in the process of these stories, either at the hand of the decayed and malignant system they’re trying to destroy, or through their own extremism, committing actions which lead you as the audience to question their ethics and humanity. After all, one person’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter, no?

Parallels and Pathetic Symmetry

You might have noticed something. These siblings sit opposite each other for a reason. The surly confidence of the Western Clint Eastwood Cowboy is diametrically opposed to the naïve guilelessness of Moana. In each case, the world they live in is the constant. They must change themselves throughout the course of the story, through personal heroics and individual decisions. But the Western protagonist is confident in their actions and does good despite the world they live in. The Eastern protagonist is resistant and must conform and integrate into the world to succeed.

For Northern and Southern stories, it’s the worlds themselves that change. Our protagonist is pretty similar. They’re both battling evil; it just depends on which side of the fence they’re starting from.

Here There Be Monsters

We should be worried about the decline of Westerns. Dystopian fiction is also way down, if we ignore the retelling of old stories (or simply reading the newspaper every day).

J.R. Tolkien hated Disney. He viewed their insipid retelling of often brutal fairy tales as destructive. Not to ruin anyone’s childhood, but in the originals, Snow White was a slave and the Hunchback of Notre Dame doesn’t get the girl – he’s hunted and likely killed.

For Tolkien, these stories survived millennia because they taught us lessons about betrayal, malice, peril, and disaster. Like the tales of the Norse Gods or sermons in the bible, they contained hard-earned human wisdom of which, as a short-lived and dim-witted species, we desperately need reminding.

So we should be worried about the disappearance of Westerns and Southerns because they teach us important lessons. Firstly, beyond the comfort of Netflix and civilised society, the world is still a pretty wild place. It’s only a tenuous mutual agreement that keeps it all together. We need to be principled in our actions, in the interest of the greater good. That takes courage. And cowboys make courage look cool, even if they happen across some buried treasure during the process.

Dystopia and other Southern genre films teach us that structures like liberty, democracy, and choice are a luxury. Society isn’t always good. It can become twisted and broken and evil. They warn us that the cost of letting these things go to shit is very high. The effort required to get them back once they’ve been lost is even higher. At best, the journey back to freedom could cost your life. At worst, it will claim your soul.

That’s not to say there aren’t lessons in the defined jawlines and banal platitudes of Captain America, or the naivety of every Disney lead since 1937 – there are. But when the sheer volume of the stories that come from Hollywood these days is so heavily weighted exclusively in a North-Easterly direction, this is bad.

When every film we watch tells us that the existing order is good, where we must conform to prosper else defend it to the death, we are missing important perspectives.

We would do ourselves a favour to consider the lessons we might be missing.

P.S. Game of Thrones is one of the most popular TV shows of our time. It’s interesting because, through the eyes of the different characters, it represents all four of these arcs at some point in the plot. Its wild popularity suggests that just because Hollywood isn’t making complex drama anymore, that doesn’t mean people don’t crave it.