La Arena

My dreams had become sand. In them, I tumbled down great dunes, grains being thrown up in plumes behind me, as dry and desiccated as the endless barren vista around me. Sometimes I would be overwhelmed by disorientation, the wind whipping the ancient powder into my eyes and stinging my cheeks. Each particle would glide past me, up the sheer cliff face of the dune before disappearing over its crest, continuing its millennial journey through the Atacama desert.

Truly, I’d never had dreams like this before. The enormity of the desert in Ica was so far from anything I’d experienced that it has lodged itself firmly in my subconsciousness. It was hypnotic because of its immensity. But also, for its inferred danger. I think part of my reaction stemmed from the haunting risk of being abandoned in such thirsty, desiccated isolation.

As much as the desert stayed with me mentally, it stayed with me physically too. After climbing one of the dunes to watch the reds and purples of sunset, I was coated with a thin film of pale dust. It clung to my hair and invaded my clothes. When I climbed back down, my shoes were absolutely full of sand. I was able to create my own mini-dunes outside my dorm room door simply by up-ending my trainers (much to the delight of my fellow travelers and staff).

Ever since the Huacachina oasis was first born, the result of an Inca princess who created the lagoon with her tears and the dunes with her running feet, it has been overshadowed by great walls of sand, 500m tall. Known as “Draas”, these behemoths creep across the desert over thousands of years, devouring all.

The Draas are fed by great sandstone hills, nearly 100 miles north. The great winds of the Pacific ocean batter these hills, slowly stripping grains from their peaks. Meanwhile, pelicans soar and boobies gather along the lips of the cliffs. They watch shoals of anchovies in the bay as they’re hunted by dolphins and sea lions. Every so often, the dark crescent of a whale surfaces, disturbing the waves with a jet of water, before it plunges back into the abyss.

All the while, slowly, the sandstone feeds the dunes of Huacachina.

It’s possible that the oasis will be claimed by these dunes eventually as sand from times before humanity existed is unearthed and starts to march once again.

As much as the Draas of Huacachina left with me, I also managed to leave something with them. As I scrambled up the sheer face of the dune (an exhausting mistake in case you’re wondering), I lost a small ring, bought in Medellin market, consumed by the sand.

My dear hope is someone finds it in 1000 years and puts it in a museum with a deep and profound commentary on what it all means.

Los Enchuffes

After a few months of traveling, I had become used to waking up with a sore head. The Pisco of Peru has that effect after a while. But this pain was different from the normal punishment of a hangover. This had come on very suddenly as if I’d be struck by a small mallet. It was strong enough to jolt me awake, hands scrabbling in the dark to find my phone so I could see my erstwhile attacker. I shone the light around my small dorm bed.

Nothing. The fan gushed gently in the dark, privacy curtain wafting gently in the breeze.

I began to sink back into my covers, eyeing the surroundings suspiciously, the gentle throbbing at my temple the only evidence of the grievous assault I’d just endured. As I lay on my side, I saw that I was looking directly into the eyes of a small vicious white monster, its metal blades winking at me malevolently. I jumped back in shock, gasping. It took some moments to realise its true form. It was just my plug adaptor, MyTravelMate ™. Blood glistened on the corner, presenting to me the side that had ruthlessly attacked me in my sleep mere moments before, on show like a wicked trophy.

It didn’t draw any blood thankfully, just rancour.

What it did give me was a sudden and inexpressible bout of homesickness. Of all the wonders of the modern world, there is one that is so often ignored.

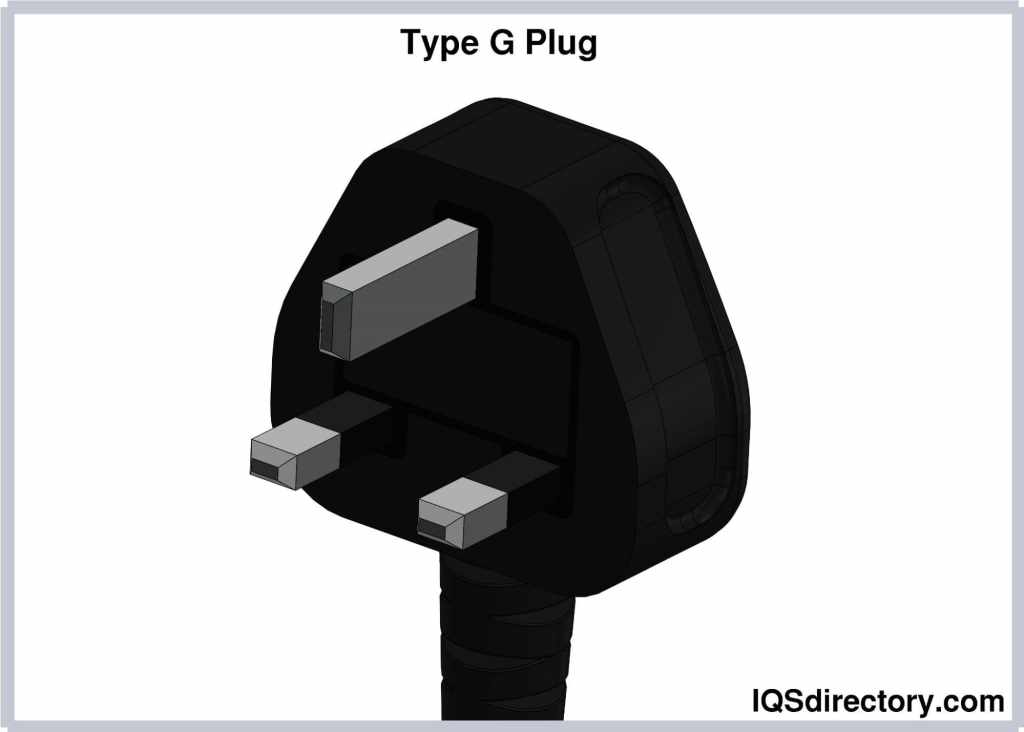

That wonder is the Tyge G plug. Its ergonomic design means it fits neatly into the hand, enabling you to connect and disconnect with ease. The third prong, solid and safe, grounds the plug. This makes sure that even if your kids stick their tongues into it, they’ll be safe from electrocution, probably. If that’s not enough, it’s the only plug in the world with an integral fuse as standard. Its shape means it sticks fast in any socket it’s introduced to.

The Type G is widely regarded as the safest plug in all the world. It certainly wouldn’t fall on someone’s head after they’d rolled onto the cable it was attached to like some of that Type B shite.

Warily, I reconnected MyTravelMate ™, moved the cable safely out of harm’s way and settled back into a deep slumber. I dreamed of England.

La Burbeja

Cusco sits 3400m above sea level. Surrounded by deep emerald-green hills and often capped by cloud. It has been home to humanity in one form or another for thousands of years – the oldest consistently inhabited place on the continent. The seat of the Incan empire before it fell into the hands of the Spanish conquistadors in the 1500s, Cusco is steeped in betrayal and bloody history.

The city is heavy and claustrophobic. The clouds feel close as they hug the surrounding mountains. The buildings are squat and the streets are narrow. The current city is built on the remains of two previous cities – the old Spanish colonial city, and the Inca metropolis before it.

Evidence of this layered sacrifice is visible. Some of the oldest buildings entomb large Inca blocks, either unable to be broken down or raided from Inca sites within the city and nearby. The unwelcome collaboration gives the architecture a disjointed, incongruous feel. It’s like mashing different colour play-do together.

When the Spanish crushed the heart of the Inca with their dreams of gold, Cusco was very briefly the centre of Spanish colonial rule in the region. But soon, as Lima became more prominent (and easier to access by sea), the city fell into degradation. Eventually, it was just another colonial backwater.

When you visit Cusco, you may find yourself one of the lucky ones. 40% of people suffer from acute altitude sickness. This is delayed onset, delivering a bottle of tequila level headache, with a vindaloo level of stomach upset. You feel tired but can’t sleep, you feel like you need energy but you can’t eat. It is like having a 2-day hangover but without any of the fun bits.

For the Wild Rover hostel, an island perched on the steep incline of one of Cusco’s sides, this is a problem. It has a beautiful vista of Cusco, looking out over the main square and the urban sprawl that gives way to deep greenery. It promises a range of activities, socialising, games, drinking, and fun. It’s a walled garden, enclosed and locked off to the outside world. Its inhabitants are almost exclusively extranjeros.

In theory, it has all the ingredients. They try really very hard to get people going but it’s an uphill battle (forgive the pun). Imagine trying to run a party where 40% of the revelers are already hungover (in this case, ill from the altitude). Then the other half need to be up at 3am/4am/5am for various treks to Machu Pichu or Rainbow Mountain.

The result is an oddly disjointed experience of trauma bonding with roommates, barely eating, and venturing into the crucible and ancient Incan civilisation for an hour before hauling yourself back up the hill to return to safety (either a lie-down or to pop a squat depending on how badly you’re suffering).

Some guests are there for mere hours until they’re whisked away bleary-eyed, pre-sunrise for their treks. Others stop by merely for a groan and a dry heave.

It’s good that the gates are locked and the hostel is secluded, lest the proud progeny of the great Inca kings see what we have become.

Los Desagues

At some point in history, the last Inca left Machu Pichu for the last time. There are many theories about why this ancient palace in the mountains was abandoned. Perhaps it was pressure from invaders? Maybe illness?

While the nature of their departure remains a mystery, we have emphatically ruled out one thing. The site was not abandoned due to drought.

Early on, toward the turn of the millennium, two people visited Machu Pichu with a rather peculiar vocation. Ruth and Kenneth Wright. They ran Wright Water Engineers (that’s right, THE Wright Water Engineers). They decided that there was more to Machu Pichu than met the eye, so they began a comprehensive survey of the water supply. What they found was beyond shocking: meticulous engineering, planning, and construction that puts modern waterworks to shame.

The Incas fed the site from a freshwater spring. Nothing new there. Except that this spring was more than 1 km from Machu Pichu. They connected the site through a canal. The canal is exactly a 3% incline all the way, to ensure that exactly the right amount of water flows to the 16 (still functioning) taps throughout the ruins. Naturally, the emperor got dibs on the first tap. But all 16 of them are perfectly crafted for the filling of Inca water vessels that were used by the other 500 inhabitants at its peak.

I know your next question. What happens if it rains? Doesn’t this overload the equilibrium of the system? Great point but no, they thought of that too. The terraces that the site is famous for are built meticulously too. A foundation of large stones, gradually reducing in size to gravel at the top not only provide a perfect base to grow crops but also offer unparalleled drainage. The terraces stop the impact of erosion. The quality of construction means that even after heavy rain, there are barely any puddles on the ground. Modern estimates suggest that to build this now, it would cost £30,000 per acre. For context, in the UK, the average size of a farm is 213 acres.

We don’t know why the Inca abandoned Machu Pichu. Perhaps we never will. But we know why the site is still there – quite simply, they built the shit out of it.

Water and Peru

The state of wastewater management is Peru is a stark contrast to the skill and planning that went into the drainage in Machu Pichu. A significant proportion of Peru’s population does not have access to clean drinking water.

Peru receives 1738mm of rain per year. That’s more than Australia, Canada, Russia, Egypt and Turkmenistan combined. But there are problems that make providing safe clean water in Peru challenging.

Firstly, the county is huge. It’s not just big in terms of land area, it also has extreme changes in elevation. La Rinconda is Peru’s highest settlement at 5,100m above sea level. Meanwhile, Lima, the Capital, is on the coast. So, running pipelines through up to 5km of mountain is hard. It’s certainly more than a 3% incline.

Secondly, while they receive a huge amount of rain, most of it falls in the highlands and the Amazon. The coast of Peru is very different, home to the northern tip of the Atacama desert, the second dryest place on earth. So that means that even if you could run pipelines through 5km of elevation and over thousands of kilometres of land, you’ll have to deal with trying to transport clean water through the desert. Very difficult.

Then, finally, there have been problems with corruption, regulation, and the systems themselves. The Rimac River which is Lima’s most important water source, is incredibly polluted. Due to the reliance on the river from the moment it starts its journey in the high Andes, right through to reaching the sea, it’s a dump for mining, commercial and domestic waste. Lack of regulation means that, despite an abundant water source, almost no one in Lima can drink the tap water.

Lack of regulation and enforcement as well as an antiquated wastewater system mean that, despite having access to water, no one can drink it. That said, the tide is turning. Peru has recently invested in the largest wastewater plan in the continent, with a focus on improving the availability of potable water throughout the country.

As a poignant moment, but one that perhaps provides some hope – the waters of the Rimac, usually brown and cloudy, ran crystal clear during the heights of the COVID pandemic.

El Trafico 2.0

His sigh was both laconic and final. Still, it didn’t stop me from stuffing my hands down the back of the car seat, scrabbling desperately at the buckle that was buried there. To no avail. After a few minutes, I took the very English decision to risk death rather than inconvenience the driver by asking him to pull over.

I’d seen some terrible things on the roads in South America, the worst being a high-speed accident in Colombia. Our bus had slowed to a crawl as we passed the smashed-up carcass of a 4×4. It has obviously been going quickly and had rolled several times before coming to rest on its side. Next, we drove past a man holding a red tarpaulin over something – the sprawled figure of a young woman, her ash-grey face contrasting with the scarlet blood that was rapidly drying in the sun. Her absolute stillness was at odds with the wracking sobs of her partner, head buried in the folds of her friend’s clothes. I never found out what happened. I still think about it. I spent a lot of the rest of that journey contemplating on what sort of gap would be left if something were to happen to me. So naturally, I put Colombia as the most dangerous place to be on the road and vowed to always wear a seatbelt. Or walk.

Then I got to Lima. Lima was a seething mass of angry traffic. It’s home to 11 million people, a third of Peru’s population. This is shocking because Peru is 5 times bigger than the UK. So, 11 million people. And all of them are in a rush. After years of politically motivated neglect of the transport system, most of the population drives (if you can call it that). Every inch of every road is contested. Taxis and buses lurch from lane to lane in an instant. The sound of screeching breaks is the tenor to the bass of antiquated engines.

The drivers here need a hair’s breadth of room. In Lima, this is known as an invitation. Then the battle of wills begins. Each car will edge closer and closer, an 11 million-player game of chicken, until paint kisses paint and someone relents to gives way.

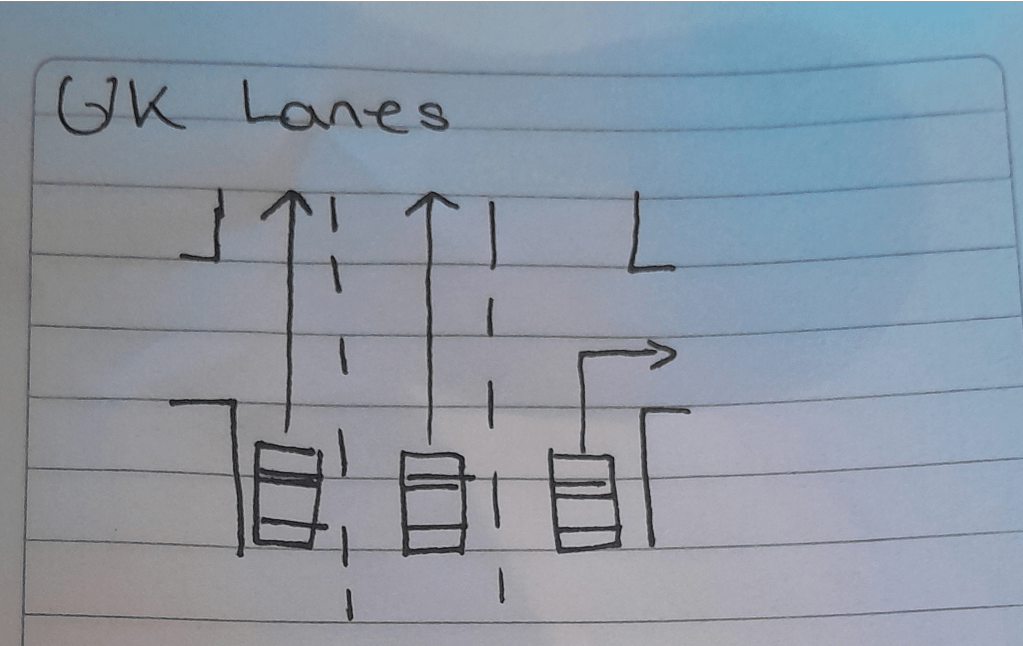

Lane discipline is an interesting one. Here’s a very technical example of how it might look in the UK:

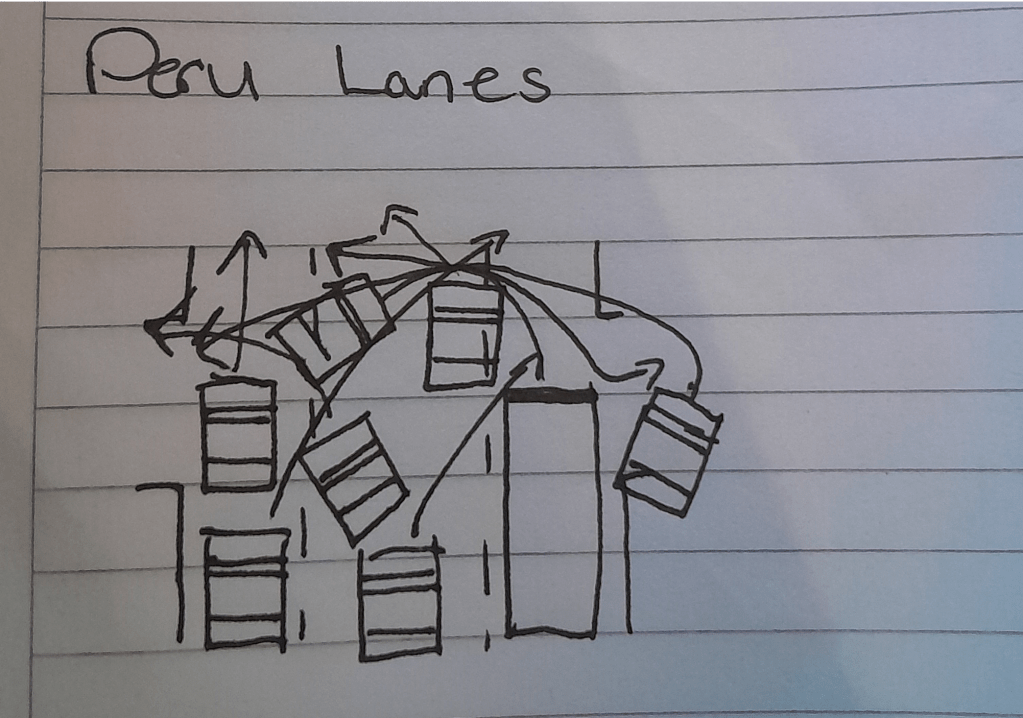

And here’s the same, very technical, situation in Peru

It’s survival of the one who cares least about their paintwork.

Of course, when you point this out to the driver, telling them how crazy and dangerous and life-threatening it all is, you invariably get the same answer.

“Jajaja… yeah” with a wolfish grin as they merge vigorously into the next lane. (for context, in Spanish texting, “jaja” is equivalent to “haha”).

And yet, for all its chaos and intensity, I didn’t witness a single accident. Not a dink nor a crash. And I took a lot of cabs during my 4 weeks in Lima. Perhaps I was lucky. But I also think that it’s possible that pressure makes diamonds and that driving in an environment like that makes you quite a good driver. Perhaps not one that Tony Gadd, the esteemed examiner who failed me at Letchworth Garden City DVLA would pass (not that I’m bitter), but in terms of their reaction times and responsiveness? I don’t know. I feel like if I was going into a high-speed pursuit, give me a driver from Lima any day – so long as I also had airbags and a functional seatbelt.

P.S. Chaotic as Lima was, driving in Atlanta, LA and Leon is more dangerous than driving in Lima.

La Comida

It could be as simple as eggs benedict. Or maybe a club sandwich. Maybe it was just a salad that was the cheapest on the menu. Whatever you’ve picked, chances are that, in Peru, you’re about to have the finest example of that dish that has ever passed your lips. And that’s just the western food. When you venture to Peruvian staples, things start to happen.

It is impossible to visit Peru and not say something about the food.

Lomo Saltado. It’s a fun-to-say rich stir fry. They use native Peruvian orange peppers, sweet and delicate in flavour. Rich tomatoes, freshly sliced, tossed with sweet red onion. Thick beef sweats alongside its fellows, as the dish is flambéed in locally distilled pisco (a grape liquor that Peru is famous for). It’s simple and bold but unbelievably tasty.

On the other end of the methodological spectrum, you could try Antichucho de huevercos – a fried and breaded fish roe in a sharp tigre base (the juice that comes with ceviche). Islands of sweet potato and fried yuca come alongside.

Or maybe a feast for the eyes, with the towering Causa de Pollo – a colourful combination of avocado, chicken, and potatoes. This is a beautiful starter or you can get a square meter of it to share.

Then there’s the chifa. This is a complete quadrant of Peruvian gastronomy that, unlike anywhere else in the world, has fused cuisines together to create a melange of Asian and Andean plates. It’s true that, to my disappointment, sweet and sour chicken balls and spareribs are lacking. But the range you’ll find on any given menu in Peru is mind-boggling.

Frankly, unless you’re very unlucky in your restaurant pick, each plate seems unique in the world and is inevitably packed with flavour – depths that are quite hard to find anywhere else. It’s inexplicable yet marvelous at the same time.

It gives the Italians and the French a run for their money. But why?

Why is this exploding my taste buds?

This is the most commonly searched English question on Peruvian Google probably. There is a real mystery about why this otherwise unassuming country packs such a punch. How can it rival cuisine that’s been perfected for more than 3000 years? Well, there are a few reasons:

- Its geography is incredibly diverse.

As we have seen, Peru gets more rain than Australia, Canada, and Russia combined, while being only a fraction of the size. And yet, a third of it is desert, and then another third is altiplano (high altitude plains of mountain, scrub, alpacas, and not much else). It is home to the northernmost point of the Atacama desert, the second driest place on earth. And yet, inland, there are rich jungles and lush farmland, still branded by the terraces of the Inca.

This incredible geographic diversity means that they can grow literally anything. That means that the vegetables and herbs you’re eating, the spices that go with it – all of it was likely grown within a day’s drive of the restaurant you’re sitting in. The same goes for meat, from the Pacific fish that graces your ceviche to the alpaca in your burger. All of it. It’s just that much fresher.

- There’s a fusion of at least 3 cultures.

Before the conquistadors, Peru was the heart of the Inca empire. Before them, there were countless cultures that all developed their own methods of cooking food. The indigenous population pioneered the cultivation of crops like maize and potatoes among many, many others. They also pioneered methods like freeze-drying, as well as cooking in clay, and roasting underground. Then the conquistadors came. Along with smallpox and slavery, they also brought rice, pork, and wheat (jolly decent of them) with Western methods of food preparation and preservation. You’ve be forgiven for assuming this was limited to frying and salt, but there was in fact more to it.

Then, during the late 1800s and the Peruvian expansion of the railroads, thousands of immigrants from Asia arrived with ingredients like soy sauce and methods like stir-frying.

The result is a fusion of 3 cultures, coming together in a way that is utterly unique to Peru.

- Biodiversity

Along with its geographical diversity, Peru is home to an exceptional number of biomes. That means that it can grow anywhere between 2000 and 3000 species of potatoes (it tends to change depending on who you ask). They have hundreds of species of pepper from the humble Rocoto pepper to the fiery Aji Charapita. From sweet to satanic.

This range means they can introduce an incredible nuance to dishes, often through combinations that are simply unknowable in the West. Imagine having a hundred different varieties of pepper to choose from, rather than the Tesco classic of “red”, “yellow” or “green”.

- Innovation

The melting pot of an incredible geographical diversity, with a rich fusion of culture and your pick of thousands of different fruits and veg, has led to a sort of culinary renaissance in Peru.

It inspires the most innovative menus and creative dishes. Peru is home to a lot of highly regarded Michelin-recommended restaurants (though shockingly it is yet to have its own Michelin Guide. It’s true that it’s a long way across the Atlantic but surely the Michelin Man can float).

Blue flame thinkers like Gaston Acurio, Virgillo Martinez or Pia Leon do amazing takes on Peruvian classics. For example, they offer menus based on different altitudes, or courses using only unique and rare Amazonian ingredients.

It’s true that some of this passion can be attributed to the diversity of its ingredients and culture. But it’s undeniable that without the Peruvian people fanning these creative embers, the culinary scene would not be where it is today.

I only have a few bits of advice. Firstly, try everything. Lomo Saltado, yep. Chifa de Pollo, yep. Brain omelette… yep, ok. Secondly, be ready to have some of the best food of your life. A double-edged sword because, for most of us, a return to culinary mediocrity is too close for comfort. And finally – elastic waistbands. Just trust me on that last one.

This is part of a series about South America. To read more about Colombia, follow the link here.

3 thoughts on “The Peru Set”