Read time: 3 mins

The ocean gate disaster has been widely reported as a failure of design. The submersible used a brittle carbon fibre cylinder instead of the normal titanium or equivalent steel that other deep sea submersibles used. Carbon Fibre is lightweight and cheap in comparison. But it also behaves in bizarre and unpredictable ways under pressure. Repeated exposure to intense pressure weakens carbon fibre.

The same effect is not observed with metal. James Carmeron’s submersible, the Deepsea Challenger, used a steel ball which is, for the most part, strong and predictable under pressure.

Another critical issue centred on the safety procedures that were built into the submersible itself. Most submersibles have safety features that mean the vessel will automatically surface if problems arise. However, the Titan used a number of features which were not fully approved or fully tested to failure.

That said, it’s possible that even the best-in-class features may not have helped due to the catastrophic nature of the implosion.

In any case, it’s safe to assume that OceanGate cut corners. There is some debate as to whether this was ideological (with senior executives on record suggesting that regulation got in the way of innovation) or if it was driven by the desire for expediency and profit (so that they could become the first commercial entity to offer trips down to the ill-fated wreck).

White Star Line

There are some harrowing consistencies between the story of the OceanGate Titan and White Star Line who built the Titanic. Nearly 200 years ago, White Star had been a global player in the development and building of shipping since it was founded in 1845. In 1910, the first supersize Olympic – Class liner came into service.

The first of the Olympic-line cruiser, aptly named the RMS Olympic, was a massive success until it collided with a Royal Navy vessel, the HMS Hawke, tearing a huge gash into her hull. The ship had to be taken into port for lengthy repairs – the repairs were expensive and delayed the entry of the second Olympic Class liner into service – the RMS Titanic. This meant there was a lot at stake for White Star Line – both reputationally and financially.

The necessary repairs for the Olympic impacted the company in 2 ways. Firstly, the collision was unexpected and the damage was extensive and as a result, very costly. Secondly, the Olympic was the White Star Line’s flagship. While it was inoperable, the company was losing money hand over foot. It’s possible that this played a part in the decisions that led to the Titanic’s catastrophe.

Materials over Matter

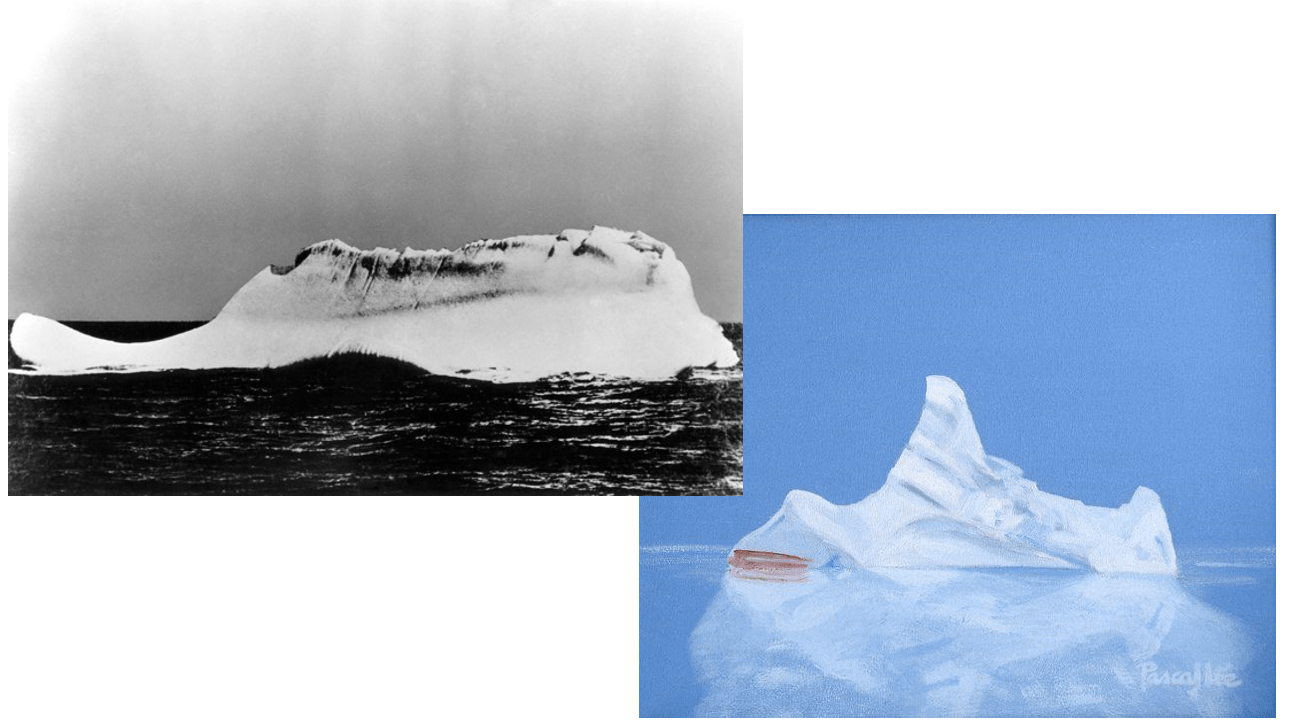

- Rivets – there are 2 theories that point to the materials used in the building of the Titanic that led to the collision being as dangerous as it was. Firstly, the Titanic used more than 3 million wrought iron rivets in its construction. Some of these were examined in 1998 and found to contain 3 times as much slag (the waste product from the smelting process) than we would consider safe for such use by today’s standards. This means that the rivets were brittle, especially at cold temperatures. When the Titanic collided with the iceberg, the tear was only a meter wide and certainly not big enough to sink the ship in 3 hours. But what if thousands of rivets sheared off simultaneously, popping thousands of little holes in the ship’s hull? This had already happened once with the Titanic’s sister ship. When the Olympic collided with the HMR Hawke in the English Channel (specifically the Solent which separates the Isle of Wight from the mainland) there are reports of hundreds of rivets popping out of her hull. If this had happened in deeper, colder water, as was the case with the Titanic, the brittle nature of the rivets could have meant more rivets popped out, which in turn would dramatically increase the volume of water pouring into the ship while also circumventing some of the safety features built into the Titanic’s superstructure – namely the watertight bulkheads separating the lower part of the ship.

- The type of steel – one of the safety features built into the Titanic was a series of bulkheads that separated the compartments at the bottom of the ship. These were supposed to be watertight. The ship could have stayed afloat indefinitely, even if one or two of these compartments had completely filled with water. The problem was that these bulkheads were made of “ordinary” steel. This is a term used at the time for lower-quality steel. Just as was the case for the rivets, the steel did not react well to extreme temperatures. This was a problem because, not only was the ship travelling through near-freezing water at the time of the collision, it transpired that the steel had been severely compromised before the voyage had even started to warp, thanks to a massive change in temperature due to a coal fire. This fire could have been burning for weeks before the ship set sail.

- The decision to sail – as with OceanGate, not all of the problems were based solely on the materials. When the Titanic set sail from Belfast where it had been built, the firemen or stokers (the workers in the bowls of the ship responsible for shovelling coal into the furnaces to drive the engines) reported the massive coal fire. Coal can spontaneously combust and burns with incredible ferocity and high heat. Moreover, it’s hard to detect a coal fire, especially when the containers holding the coal were over 3 stories high. The coal fire burned for days after it had been discovered, with temperatures reaching as high as 1,000 degrees centigrade (1,800 degrees Fahrenheit). Coal fires were common on cruise liners like this but the severity and impact of this coal fire was visible from the hull, where a black mark is seen in photos from when the ship left Belfast to when it arrived in Portsmouth. The fire clearly had an impact on the psychology of the workers below deck. When the vessel reached Portsmouth, only 8 of the original 100 firemen stayed with the boat, the rest deciding to stay ashore. The fire took days to put out. It had been burning hour after hour in direct contact with one of the bulkheads that supposedly made the ship unsinkable. There was evidence that the metal had been red hot, and first-hand reports of warping. What the workers would not have known at the time is that “ordinary” steel, when subjected to that kind of heat, loses 75% of its strength. When the Titanic hit the iceberg, the damage meant that the bulkhead simply popped open under the water pressure from the compartment next to it.

A Cruel Mistress

So, the Titan sank because it used a carbon fibre shell, that hadn’t been properly tested or approved, and that weakened over repeated usage. Proper testing and approvals were not allowed, due to the executive team’s view that regulation stifled innovation and a desire to generate profit quickly. Together these decisions meant that the submersible imploded within nanoseconds of the chamber being breached. The Titanic sank because poor-quality rivets had been used, letting significantly more water into the ship than anticipated. This was likely because White Star wanted to cut costs thanks to their flagship Olympic being inoperable and needing repairs. Then, a coal fire significantly weakened the one thing that could have kept the ship afloat – the watertight steel bulkhead. The decision to set sail despite the coal fire could have been partly driven by the delays in bringing the Titanic into service and the desire to start generating profit. When the rivets and then the bulkhead failed, the Titanic sank in less than 3 hours, all 52,000 tons of it.

They sank in the same part of the Atlantic Ocean, nearly 100 years apart. But while time and technology can change, each event gives a stark reminder that the sea is a cruel and brutal place that will punish the cutting of corners with cold indifference.

To learn more about the evidence surrounding the sinking of the Titanic, there is a great documentary from Channel 4 which you can watch here.

Smarticles provides short-form curated pieces about history, psychology, science and technology, directly into your inbox. You can explore the full catalogue for free, here.