Read Time: 15 mins

We take spice for granted. It’s safe to say that modern humans have the most varied palates in history, enjoying cuisine and flavour from every corner of the world. These flavours have mixed and melded, creating brand-new fusion cuisines. We have also created our own artificial spice, things like MSG or aspartame, which push the boundaries of what our ancestors could ever conceive as possible in terms of flavour.

The most famous “spicy” spice is of course the chilli pepper. Chilli peppers had been a mainstay of indigenous South American cuisine for many thousands of years, originating in Bolivia before being properly cultivated in Mexico. It was discovered by Western cuisine in the late 1400s as part of what’s known as the “Colombian Exchange”[i]. The potency of the spice was incredible, mainly due to the presence of the chemical Capsaicin. This unique chemical activates nociceptors (or pain receptors ) which causes the hot sensation (or piquancy). In short, it’s the thing that makes your friend who doesn’t like spice splutter and cry, cursing your name through stinging lips.

It wasn’t long before Chilli took on a life of its own and became prevalent in almost every cuisine globally. There is an ongoing competition to create the hottest chilli in the world. The current Guinness World Record is held by the Carolina Reaper, but the competition continues.

What’s the right way to taste chilli pepper?

The masochists who participate in chilli-eating competitions tend to have specific things they look for when judging new Chillis. Each type has its own flavour profile. Anyone who has had a jalapeno knows that it hits differently from a bird’s eye. A bird’s eye scalds in a slightly different way to a Scotch Bonnet.

To describe the overall sensory experience, there are some widely recognised terms in the chilli-tasting community. They describe different chillis in terms of their development, duration, location, feeling, and intensity:

- Development: Refers to how the flavours and heat of the chilli pepper evolve and change as you taste it. This can include the initial taste, how the flavours meld or transform on the palate, and any lingering aftertaste. Different chilli peppers may have unique development profiles, with some offering a quick burst of heat followed by a mellowing of flavours, while others may slowly build in intensity.

- Duration: The length of time that the flavours and heat of the chilli pepper persist in your mouth. Some chilli peppers have a short, sharp burst of heat that dissipates quickly, while others may have a more prolonged and lingering spiciness that can last several minutes or longer.

- Location: Refers to the specific areas of the mouth and throat where the flavours and heat of the chilli pepper are most prominently experienced. Some chilli peppers might have a more localized sensation, such as on the tip of the tongue or the back of the throat, while others may provide a more widespread sensation throughout the mouth. Others blast their way up your nose.

- Feeling: Describes the physical and sensory reactions experienced when tasting chilli peppers. The sensation of heat or spiciness can vary, with some peppers producing a mild, warming sensation, while others may cause a more intense, famous burn. The feelings can be sharp and tingling like pinpricks, or more of a flat warmth throughout the mouth. The capsaicin in chilli peppers also tends to trigger the physiological responses we enjoy such as sweating, tearing up, a runny nose and violent requests for milk.

- Intensity: The level of spiciness or heat experienced when tasting chilli peppers. Intensity can vary significantly depending on the type of chilli pepper and an individual’s tolerance for spiciness. The Scoville scale is commonly used to measure the intensity of chilli peppers, with higher Scoville Heat Units (SHU)[ii] indicating hotter peppers. Intensity can range from mild and barely noticeable to extremely hot and overpowering. As a case in point, we also measure pepper spray in terms of Scoville units.

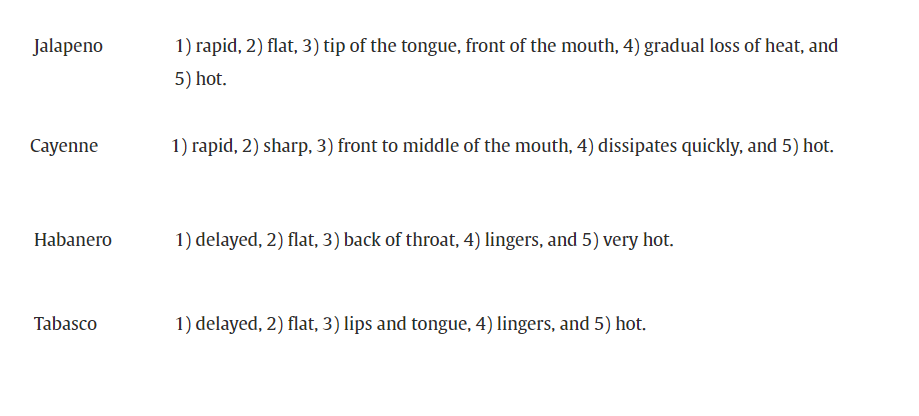

Here is a table of some famous chilli peppers using the above heat profile:

But what did we all eat before 1492? And how come other spices are spicy? Would any fit into the 5 categories above?

The Spices of the Old World

Before the discovery of Chilli peppers, most of the spices we know were popularised and introduced into Western cuisine by ancient Roman trade routes. You can find many of these spices as key ingredients in the earliest surviving written cookbook, known as Apicius or “De re coquinaria”. Composed of countless generation-older texts, it contains nearly 100 recipes for everything from a re-invigorating honey wine for travellers to sauces and glazes for meats, mushroom dishes and salads. There remain some mysterious ingredients and spices which continue to baffle translators. However, other spices are very familiar – things like ginger, mustard, garlic and of course black pepper were heavily utilised. Needless to say, the below is for entertainment purposes only – please consult a medical professional before rubbing mustard on your broken arm or some such.

Mustard

Origin and history

Mustard has been part of the cuisine for more than 5000 years. It was originally written about in texts from India and Sumaria (ancient Persia) and was cultivated in Egypt. The more condiment style mustard was developed by the Romans who used to soak the mustard seeds in wine. This is where it gets its name. The Roman’s fascination with mustard led to it becoming cultivated throughout Western Europe, eventually becoming centred in Dijon in the 13th century. In the early 20th century, it was refined by the English. It became the largest spice by volume in the spice trade. Its popularity has varied along with the style and type, from classic Dijon mustard to the yellow American variety.

Why is it spicy

Allyl isothiocyanate– insecticide, anti-mould, bactericide, and nematicide and has been shown to have desirable attributes of a cancer chemopreventive agent. The seeds are a good source of selenium, an important micronutrient that supports thyroid function and Omega 3 (although it’s worth noting that the health benefits of omega 3 have been widely disputed in recent years). It’s about as lethal as the drug MDMA (or ecstasy) or the insecticide DDT.

Types of mustard

- American yellow mustard – uses a large proportion of Yellow mustard seeds which are less piquant. This type also contains much more vinegar than other varieties, impacting the flavour and making it cheaper to produce.

- Dijon Mustard – a specific type of mustard originally prepared in 1856. This style originally used “verjuice” which is the juice of unripe green grapes. Most modern preparations use white wine instead.

- English Mustard – it is one of the hottest styles of mustard and uses yellow and brown seeds with relatively little vinegar or acid content. This creates a potent mixture compared to other types on this list.

- French Mustard – is actually a brand name invented by the English mustard manufacturer Colman’s. It’s typically sweeter and brown in colour compared to other styles.

- Horseradish / Wasabi – these get an honourable mention because they rely on the same chemical compound for their pungency, although they are cultivated from an entirely different plant. Wasabi is actually very difficult to cultivate because it requires moist but not wet soil at a stable temperature and is susceptible to disease. Not one for the English garden.

Garlic

Origin

Garlic is one of the oldest foodstuffs we know of. It is believed to have originated from central Asia, and it’s the first known herb to be cultivated by man. It was cultivated as far back as the Neolithic period (from around 10,000 BC to 4500 BC). Over many years, following the migration of humanity, Garlic worked its way to Africa, being used extensively by the Egyptians. In fact, it was so valuable that Tutankhamun was buried with lots of actual garlic, as well as some garlic bulb-shaped ornaments.

It spread to Europe and formed an important part of Roman and ancient Greek cuisine. In modern times, it is almost exclusively cultivated in China which is responsible for more than 70% of the world’s production. In China, prison labour is often used to process garlic because it’s quite hard to process with machinery.

Why is it spicy?

Allicin – this chemical is both anti-bacterial and anti-fungal. It’s currently undergoing cancer trials, however, these are inconclusive. That said, a small study found an effect in preventing the common cold, although later, this trial was reviewed for its methodology and scientific rigour and so the results were discredited. In pure form, it’s slightly less toxic than Uranium, but more toxic than the active ingredient in Mustard (Allyl isothiocyanate)

Types of Garlic

- Allium longicuspis – as close as we can get to the original garlic that was cultivated by our ancient ancestors to create all of the other types we know today.

- Allium sativum – the common garlic that is produced in millions of tonnes throughout the world.

- Solo garlic – Very similar to common garlic, except it is made of a single bulb

- Aglio Rosso di Nubia – a protected garlic from Sicily. It’s harvested in soil that rotates each year with the plants of the Paceco Yellow Melon. It has a notably high concentration of Allicin which gives it a very pungent and intense flavour.

- Wild garlic – is not actually garlic. Wild garlic is actually more closely related to the onion family. Onions are also a source of allicin which is why they also have a similar unique taste and spice profile.

Pepper

Origin

Black pepper was first described in Indian texts from around 2000 BC, in India where it flourished in the wet monsoon climate. Prior to the introduction of chilli peppers, once they were discovered in the Americas, black pepper was a staple spice of Indian cuisine. It became a central tradable good between the East and the empires of Rome and ancient Greece, earning it the name “Black Gold”. The pepper trade was incredibly important and provided a readily tradable and universally valuable asset that people from both East and West coveted. So much so that people would pay rent with black pepper at various points in our history.

Why is it spicy?

Piperine – The active chemical that gives black pepper its pungency is called Piperine. It is currently undergoing research and preliminary studies suggest it may have anti-inflammatory properties (helping with things like rheumatoid arthritis). It also assists the “bio-availability” or efficacy of other chemicals and drugs in the body, making them easier for the body to process. Pure piperine is more toxic than capsaicin and marginally less toxic than heroin.

Types of Peppercorn

- Black pepper – the classic peppercorn is made by picking the green, unripe peppercorn fruit and then drying them out.

- White pepper – just like black pepper, white peppercorns are soaked and dried in the sun, however, they have had their skin removed. They tend to have a lighter flavour than other types of pepper.

- Green pepper – made from unripe peppercorn fruit and is usually soaked in vinegar or brine or directly freeze-dried or dehydrated. Any of these processes mean that the peppercorns retain their green colouration. They are known to be the mildest of the varieties.

- Red pepper – made in the same way as green peppercorns except they use the ripe fruit before the pickling/brining or drying process. These tend to be rare and offer a more fruity flavour.

- Pink pepper – is not from the pepper plant, but actually refers to one of three different plants originally from South America. They are often more fruity in flavour and don’t have the same kick one would expect from true pepper

- Sichuan pepper – this is another false friend and is not related to black pepper. Instead, it’s in the same family as oranges and lemons. The berries contain a different chemical, called hydroxy-alpha-sanshool, which is responsible for the numbing and tingling sensation of Sichuan pepper. Chemically, it is more closely related to capsaicin from Chilli peppers than piperine in black pepper.

Ginger

Origin

Ginger is the world’s oldest traded commodity and was cultivated in China more than 4000 years ago. Strangely the plant does not grow in the wild nor can it be cultivated by seeds. Instead, ginger is cultivated by dividing the root into different parts. Traded from India to Rome, it was incredibly popular but almost disappeared with the fall of the Roman Empire, after which the Ottoman Empire took over the spice trade. They levied significant taxes which, when combined with the relative difficulty in the cultivation of ginger, led to the spice almost disappearing from Western cuisine. This remained the case until it was secretly exported to the Caribbean where it flourished, providing a new avenue for a reinvigorated ginger trade to Europe and the Americas.

Why is it spicy?

Gingerol – Ginger is currently undergoing multiple studies for a wide range of impacts that it may have on humans. According to ongoing research, ginger has the potential to be:

- Anti-inflammatory

- Anti-microbial

- Anti-cancer

It is also being looked for its impact on:

- Cardiovascular diseases

- Neurodegenerative diseases

- Diabetes

- Chemotherapy induces nausea and emesis

It is the most widely studied chemical on the list and is abundant in various forms in ginger root. Gingerol is deemed safe for humans, theoretically safer than paracetamol or THC, although it does have some interactions with drugs like Warfarin (used as an anti-coagulant) and Nifedepine (a high blood pressure medication).

Types of Ginger:

- Fresh ginger – the root can be eaten raw, pickled or cooked. It can be grated, cut and juiced.

- Dried ginger – when ginger is dried, it releases a related set of chemicals called shogaols. These are responsible for the more pungent and spicey nature of dried ginger compared to its fresh counterpart. In relative comparison, shogaols are more pungent than the active ingredient in black pepper but less than capsaicin.

A sophisticated palate

What’s striking about every single one of these spices is the impact they seem to have on health. In one way or another, the active ingredient in each spice, all of them valuable ancient commodities, is currently under investigation for some health benefit or another.

When it comes to taste and flavour, there is often an evolutionary explanation – sugar tastes sweet because it gives us energy, salt aids our heart and blood, meat or mushrooms have that deep umami flavour because of protein and things that have gone off or are poisonous often taste sour or bitter.

It would be curious to understand if these different spices are something that we are born to appreciate (although perhaps more subtly than salt and sugar) or something we acquire. And do we acquire a taste for them through sheer exposure, or does our body begin to appreciate these spices more as we age and become less adept at fighting off the illnesses and malaises of life?

In any case, if there’s one thing that is almost certain – there was part of you that thought about trying out one of those ancient Roman recipes.

[i] The Colombian Exchange – named after Christopher Columbus. It refers to the purposeful (or accidental) transfer of old-world species and new-world species. Some pantry spice staples are featured in this list. Here’s a list of plants that were brought to the old world:

1. Maize (Zea mays);

2. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum);

3. Potato (Solanum tuberosum);

4. Vanilla (Vanilla);

5. Pará rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis);

6. Cacao (Theobroma cacao);

7. Tobacco (Nicotiana rustica)

And here are some old-world plants that were spread to the new world:

1. Citrus (Rutaceae);

2. Apple (Malus domestica);

3. Banana (Musa);

4. Mango (Mangifera);

5. Onion (Allium);

6. Coffee (Coffea);

7. Wheat (Triticum spp.);

8. Rice (Oryza sativa)

It’s also worth noting that chilli peppers are called that because when the continent and spice were first discovered by the West, they thought they’d found India and as such, Black Pepper. Learn more about the Colombian Exchange here.

[ii] Scoville Heat Units (SHU) are used exclusively to describe capsaicin-containing products. The measure was originally subjective and involved extracting the capsaicin from chilli peppers by soaking them in alcohol before mixing them with sugar water. Then, you would provide the solution to some qualified tasters until at least 3 are unable to taste the heat anymore. Of the chemicals on this list, Allyl Isothiocyanate from Mustard, Wasabi and Horseradish is the only water-soluble chemical (and then only slightly) which is why it is the only one that could theoretically have anything similar to a SHU score. New techniques have allowed for an analytical process to understand the exact capsaicin content of a given chilli. Find out more here.