Read Time: 25 mins

Swiping. A word that used to be used to describe a theft (or a sudden and vicious attack), has taken on an entirely new meaning. Swiping left, swiping right. People are now swiping to decide their reproductive future (or not, as the case may be).

Recent perspectives on dating apps are frankly bleak. There is a deluge of commentary, all arguing that dating apps offer nothing but despair. They are a petri-dish for offensive or upsetting behaviour that is barely moderated. And to make matters worse, they toy with one of the most fundamental and addictive aspects of humanity – our desire to love and be loved.

And yet, these apps remain some of the most profitable tech platforms in the world, with millions of monthly users.

This wasn’t always the case. When they started out, dating apps were not profitable at all which was a problem for the companies developing them.

In order to get to where they are now, they had to steal ideas from another tech institution, one that had been developing and honing its craft for nearly 30 years – the humble video game.

One of the biggest challenges for the modern singleton is that dating apps have taken the lessons learned by big video game studios and built on them. But they’ve done so in a world that has almost no regulation. And, while video games may be damaging because they waste our time and attention, dating apps latch onto something far more primal and as a result, far more powerful. The impact when things go wrong is likely to be much more insidious, far-reaching and damaging than anyone could have first imagined.

So what did video games learn? And how did dating apps steal their ideas?

The Master

Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 is what’s known in the industry as a triple A title. It’s huge. It hit $1bn of revenue in 10 days. This is incredible for any media. But this sort of success doesn’t happen overnight. It’s the result of decades of optimised enhancements and tweaks, all designed to increase a gamer’s propensity to buy.

One of the biggest problems facing the video game industry in the mid-2010s was how to ensure that their games continued to make money.

Back in the golden age, you would buy a disk or a cartridge that was fully formed. It had everything. All the characters, stories, gameplay, maps and edge of your seat action, all packed into this one little disk.

The problem for game studios was that once you bought the game, that was it. You could sit there and sink hours into their intellectual property without having to part with a single penny more. Great for the gamer. Bad for the studio.

Sequels

In the early days, studios tried to capitalise on this by cranking out sequel after sequel, as fast as possible. Sometimes they would be wildly successful. Sometimes they would go very wrong. It doesn’t matter what franchise you look at, there is at least one title from this period that was so rushed and badly developed that it became an in-joke for the community, leading to a £1 sticker and the bargain bin within weeks. In other cases, people simply stuck with the old games that they knew worked. The game studios needed a new plan.

Microtransactions

The advancement in cloud technology meant that studios could start to deploy new characters, maps, skins, weapons, cars, paint jobs and stickers and pump them directly out to your console. For a small fee (anywhere between £0.50 and £30) you could “own” these virtual items. The move was genius as it meant that studios could ensure a constant revenue stream from gamers, with some spending hundreds of pounds, often orders of magnitude above their initial investment in the game, in order to collect all the items.

But all was not well. Just as the move to create sequel after sequel to generate revenue failed, the microtransaction did too – except this time, game studios bumped into legislation designed to protect children.

In this early period, games used a “Loot box” mechanic. Gamers would pay for access to a loot box. The type of loot box (let’s say gold, silver and bronze) would define what type of content you would get and how valuable it was likely to be. However, the actual content of the box would be random, the probability set by the game studio. This meant that gamers, especially younger players, would end up spending hundreds (often from the bank of mum and dad) in order to find a specific item from this “randomised” loot box system. Great for the studios. Bad for the consumer. Eventually this mini slot machine mechanic was picked up by regulators, and after enough complaints, the “Loot Box” was deemed to be gambling and banned.

So the game studios couldn’t keep developing games all the time. It put too much strain on development and fatigued the player base. They now couldn’t mug gamers into parting with cash by using the deep rooted and addictive psychology of gambling.

They needed something new.

Matchmaking

Skill-based Match Making (SBMM) is an algorithm that has been baked into modern video games. It is marketed as creating a fair and enjoyable experience for gamers. The idea is simple. The algorithm matches players based on their relative skill. The games are more intense and fun by virtue of the fact that a person who’s sunk 700 hours into the game doesn’t destroy a new player or “noob” so completely they hurl their controller across the room. Seems to make sense, right?

According to its creators, skill-based matchmaking also serves a different purpose. It doesn’t matter how much better you get, the algorithm keeps you more or less at the same level, albeit with other people who about as good as you are. This means that while you are getting better at the game, you never feel like you’re getting better at the game. You are constantly held at a mildly frustrating median – just enough so you keep losing, which activates the competitive part of your brain, yet winning enough that you want to come back and play again. So, SBMM keeps you playing. That is good for the game studios because it means that the games get more screen time and more attention from players. This provides more of a window for gamers to fall victim to the second thing that SBMM does. During its player selection for games, SBMM will put you in matches with players who have bought loads of stuff from the online store. Flaming heads, famous costumes, neon pink flashes and unique dances or executions. Things that you might like yourself. Then, it selects players who are slightly better than you and puts you in a match together. These players will reliably score more goals, get more kills, win more races etc.

Put those things together the result is that a standard player is hooked into spending more time on the game, while being beaten more than average by a player who has spent loads of money on additional content. This not only gives more exposure to the buyable content, but it creates an association between the buyable content and being good at the game.

How do they know what you’ll like? The regulation around video gaming is often more lax than other tech platforms. This is part of the reason it took so long for regulators to act on the “loot box” scandal. All of your data (which is actually far richer and deeper in video games than you might initially consider) is for sale to the highest bidder.

For example, video games can track the nuance and differences in:

- Route planning

- Decision making

- Buying propensity

- Fashion preferences

- Response to stress

- Colour processing

- Motion processing

These are useful data points but they are all relatively narrow, based on things that only really have context in the world of the game. But what if that game was based on your romantic preferences? What kind of data could be tracked?

The Student

Going on a date with someone is scary. You’re nervous. Of course you are. You like the other person enough that you’re willing to spend time and money getting to know them. You’re willing to become a little more vulnerable and hope they reciprocate.

Dating apps have created some incredible opportunities for people. Something like 25% of new relationships now start online. For a lot of different groups, they have often provided safe and non-judgemental places for people to meet others like them in a way that was never possible before.

But in the beginning, the apps just didn’t make any money. That needed to change, so they started to look at the master, video games, to see if there was anything they could borrow to start turning a profit.

Sequels

Tinder is the largest dating app on the web. It has over 10 million users (75% of whom are male). It pioneered a new kind of dating, the now famous “swipe” mechanic. This had never been done before. And with this, Tinder swiped its way to a staggering level of growth – when merged with Match.com in 2017 it’s growth accelerated even more. It now boasts revenues topping $1.6 billion.

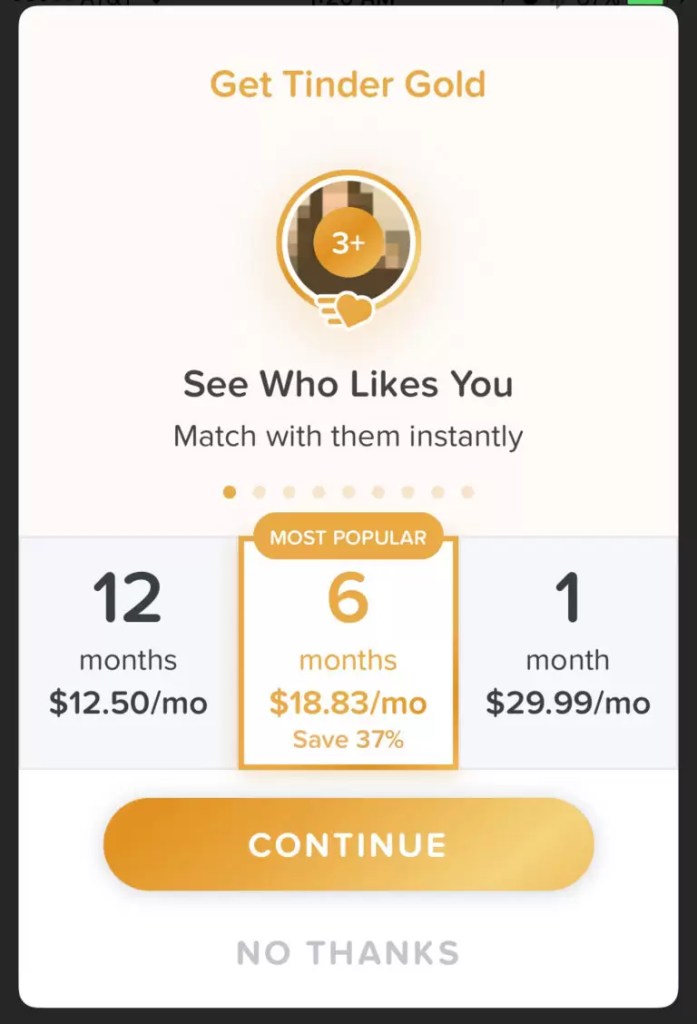

The problem facing Tinder was how to monetise the platform. An ad-model could only take them so far. One of the best types of revenue for a company is subscription services. To begin, Tinder released its first premium service, Tinder Plus. You were able to have unlimited swipes (albeit it, the app punished older people with a higher price tag).

Lots of people bought the sequel. Tinder increased its paid user count that year by nearly 1 million. After this came Tinder Gold, with a host of new gamified features, including changing your location or reversing your decision to swipe someone. In 2020, another sequel, Tinder Platinum, was released which contained other great features, such as the ability to message people without their consent via the “Superlike” functionality.

The upshot was that every dating app released a sequel. But like the video game studios before them, there’s only so many sequels you can make. So where could they possibly go next?

Microtransactions

Hinge is another modern dating app. It’s different because you can include more about you in your profile with predetermined hints and questions. They say this means that matches are down to more than sheer, unadulterated sex appeal (as is the case in other apps like Tinder), but rather personality. Like Tinder, it was also hoovered into Match Group’s monopoly in 2018. While this might lead to some anti-trust concerns (Match Group has nearly 50% of the online dating market in the US), the more interesting thing is how these apps introduced the microtransaction.

Hinge developed a new tab in 2020 called “Standouts”. Naturally, due to the incredible amount of data the apps collect on users (topping 800 pages of data in some cases), the algorithm understands which people are getting the most attention. They can track the time you linger on a page, the time you look at photos and most obviously, the number of likes a person gets. The “Standouts” feature puts the most statistically attractive potential partners behind a paywall. To access them, users need to buy “Roses”. These are nearly £5 each. Equally, Tinder has its own form of microtransaction with the “Superlike – a feature which means you can show someone you really like them by demonstrating you’ve paid to give them attention – or the “Boost” which promised users more exposure to other users; for a fee. Bumble has done the same with their “Spotlight” features.

In each case, whatever brand you choose, the dating apps have lifted another trick from video game studios – generating a steady stream of revenue from committed users through microtransactions. The difference is that they are safe from the gambling loophole. Why? While it’s still a gamble to send someone a “Rose” or a “Superlike” (as you might not get anything back) it has nothing to do with Hinge. They’re not putting anything in random boxes. They don’t set the probability for the slot machine. But they do get your money. This means that they are able to safely extract cash from users with exactly the same gambling psychology as the loot box – except this time, without any risk from regulators.

Matchmaking

Early renditions of Tinder were simple. A user set a radius to look for other users and the app would surface accounts for you. These searches would be based on some simple criteria set by the person using the app. Then your brain would do the rest. You’d see if you liked their picture, their profile. You’d arrange a date and see if you liked them in person. In its simplest form, it did what all good technology should do. It made life easier by removing blockers that would otherwise get in the way. The app drew people together who may never have met through chance in real life. It did so in a way that seemed simple and understandable to the users. This was true for the initial concepts for more or less all of the dating apps.

The problem with this from a business perspective is significant. Firstly, if you let the user make decisions outside of the app, you can’t track their data as effectively. This means lost revenue. Secondly, people are quite good at fancying other people, which means the chances of finding someone you actually like with this simple model are quite high. If your app is getting people to marry each other more quickly and happily-ever-aftery’y, this is a serious problem.

Whether the revenue from your app is based on subscription, advertising, microtransactions or selling user data, there is one thing you need. Screentime from as many users as possible. So the apps have learned once again from video games and developed algorithms. These are marketed as perfecting your dating experience. In truth, in exactly the same way as video games, allegations from insiders suggest they are tweaked to promote buying behaviours. The apps will promote statistically more attractive profiles when it’s time to renew your subscription. They’ll restrict access to profiles you find attractive if you let you subscription lapse. In some cases, it’s been suggested that some apps will even use attractive bots to “anchor” users and keep them swiping.

While the exact nature of the algorithms are a closely guarded secret, what we do know is that dating apps have spent most of their existence copying from video games companies. It’s hard to imagine that they simply stopped when it came to the advances that video games made in terms of changing the algorithm to increase a user’s propensity to buy. The apps are certainly not designed to be deleted.

Game over.

So, millions of people are at the mercy of an unregulated and opaque system that is becoming increasingly pay to play. On one level, it uses tricks that ensnare our primal urges and the brain’s reward system. On the other, it controls and strangles our innate need for intimacy and affection.

One problem is that the design of these apps offer a very narrow view of people. They tend to focus users towards two specific aspects – physical attractiveness and social status. These are the easiest to showcase through a few pictures and lines of text. The result is an ocean of status signalling – skiing holidays and professional photography, exotic locations and designer gym gear, fast cars and big brands.

In reality, while physical attractiveness and social status are important, there are other factors that come into play that the apps completely miss. Factors such as kindness, intelligence and shared values, all of which are really important but much harder to convey in 6 photos and a pithy comment about pineapple on pizza. As a result, their value is downgraded in favour of status based content.

Young people stepping into this world are under pressure to imitate what they see. The environment heavily promotes the idea that the only way to be successful is to demonstrate physical attractiveness and high social status at all costs. By extension, other virtues such as kindness, intelligence and discussions about values are seen as less important. Their intrinsic value in the world of the app is downgraded. And, as is the case for so many young people these days, if this represents the only exposure a person is getting to the outside world, then the intrinsic value of things like kindness and intelligence is downgraded in real life too.

Something else that is interesting is that the apps encourage you to select based on your own criteria. This self-limitation means that users stop meeting people with different perspectives, points of view, ways of communicating or ways of thinking. The result is a kind of dating echo chamber where users select for traits they think they want or need. The question is, do people really know what they want in a partner a priori and if not, is it a good thing to filter out a huge percentage of people without hesitation.

The demographics of these apps is a significant cause for concern. In the USA, men make up roughly 49% of the population. On Tinder, men make up 75% of the user base. Think about that. There are 10 million users on Tinder in the US. So, if every single girl hooked up with a different guy on Tinder, there would still be 5 million men left. This issue is compounded when one considers that men’s and women’s swiping behaviour is very different. Men’s swiping behaviour is volume driven. Statistically, their preferences follow a bell curve when swiping through profiles. Women on the other hand are far more selective. More often than not, the top 20% of male profiles (typically those which are more physically attractive and demonstrate high status) will hoover up a mammoth 80% of the swipes from women.

The fact that women are more selective than men isn’t news. It has been shown that the odds of a man jumping into bed with a women simply from being asked are pretty high, especially when compared to women asked the same question (see Hatfield & Clark’s work). But the apps offer an unusually selective environment with incredible amounts of casualised rejection, which ranges from simply not getting any matches through to things like “ghosting” where users suddenly stop talking to each other.

In real life scenarios, partner selection is much more balanced, which is good. People tend to weigh status and physical attractiveness less intensely. The other factors like kindness, intelligence and shared values come into play – demonstrated through little things, non-verbal cues and intuition. These are all things which are inherently good for society. Rejection is a part of courting behaviour and has been for millennia, but in real life situations, there is more pressure to communicate effectively and civilly (usually because the courter is stood in front of you, which often inspires a kinder approach).

However a lot of young people, especially young men, are rarely in real life scenarios anymore (especially post COVID). They’re going out less, seeing fewer people. They’re less likely to go to college and network. They have fewer friends and spend more time alone than ever before. Then they turn to a dating app and are met with an ocean of rejection. But due to several decades of “coddling” (as defined by Jonathan Haidt) and the relatively new status of this technology, young people are not as equipped for rejection as their parents. So the rejection cuts deep and further fuels a feeling of isolation. Isolation can easily turn into bitterness, anxiety, depression and other mental health issues. This is bad for society. There is a significant correlation between feelings of isolation, rejection and vulnerability and radicalisation in young men – just look at the demographic most responsible for school shootings in the USA.

Rematch?

Technology has incredible power to connect people in ways that were unimaginable even 100 years ago. But when this power is turned back on its users to exploit them and generate profit, it’s a recipe for disaster. And when this dangerous power coalesces with something as primal and potent and love and sex, then it can do significant and lasting damage if not managed responsibly.

It would be great to see a return to the things that dating apps are really good at. This technology has had an incredible impact for cross cultural engagement, for minority groups and LGBTQ+ communities. Post COVID, the tech could help supercharge people reaching out to others in their local community in various different ways.

It’s fair to say that over the past few decades, traditional ideas around sex and dating have been turned on their head. Gone are the days where you had to settle for the person in your village because they were the only person available. The empowerment of women and connective technology now means you can date people from different backgrounds, cultures, religions, cities, countries and continents. This is seen by some as experimental and by others as freeing – just as the counterculture was in the 60s.

In their purest form, the apps remove barriers that would otherwise stop people connecting with each other.

So how can the apps become the good guys? They should promote the ideal of openness and connection. They should be open source so anyone can build their own dating app. The data they collect should be transparent, with the ability for users to opt out of data collection if they wanted. Users should have the option to turn off the algorithm and roll the dice, as in real life. And, importantly, there should be more study and regulation around the impact that these apps have on people’s mental health. This regulation, at the very least, should be geared to help stop the strip mining of intimacy and profiteering from people’s innate desire to love and be loved. Even with the above caveats, there is still plenty of scope for the apps to make money, but the incentive would be different. “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the behaviour” is a famous quote from Charlie Munger, the Vice Chairman for Warren Buffet’s Venture Capital firm, Berkshire Hathaway. Better regulation would lead to better incentives which would lead to dating apps providing a more balanced, healthy and positive experience for users. This would be positive for society.

On the other hand, people should be encouraged to meet more people in person and relearn how to connect without relying on prompts and pictures. This is as true for dating apps as it is for social media. Engaging in real life small talk helps us decide if someone is kind or intelligence or funny. It helps us develop our ability to communicate properly. It teaches us tolerance. And, as a plus, we intuitively learn more about what we are looking for in a partner and what were weren’t looking for in a partner but like anyway. Very often, it turns out that the things we weren’t looking for in a partner tend to be exactly the thing we needed.

The world of dating should be fun and messy and surprising. It should not be arbitrary and algorithmically defined.

For more on dating apps and the potential impact they’re having on society, check out Rob Henderson, a Psychologist with the University of Austin. You can view his website here.