Read Time: 10 mins

Everyone wants you to pay attention. Recent exposes about the goose step of big tech into our minds and wallets has got people thinking more about their attention and where its spent. While Netflix has thrust documentaries like The Great Hack (2019) and The Social Dilemma (2020) into the public eye, there is a whole history behind tech monoliths like Facebook, Amazon and Google and the advertising model that drives their profits. This history is one of how our attention has been increasingly and now unceasingly manipulated.

In his book, The Attention Merchants, author Tim Wu introduces us to generations of pioneers; advertising frontiersmen who have refined the taking of your money by harnessing your attention. It’s essential reading for anyone who wants to understand the evolution of the “ad-man” and the funny ways that society pushes back once this ever hungry enterprise has overstepped the boundaries of our social contract. What follows is a potted history of the attention merchant, inspired by Tim’s book which is linked below:

Snakes, Posters and Sex on the Moon

“You disgust me sir and I shan’t stand for it”

For the average cap in hander of the early 1800s, newspapers were rubbish. They were expensive and boring. The Sun, a British newspaper now more popular as overpriced kindling, once published stories like “Forest of Dartmoor.”, concerning the potential repurposing of land for agriculture, or a notice of the publication of Guthrie’s Geographical Grammar, a map book – a stark contrast to the lurid and loud stories adorning today’s newsagents.

A nail biter from The Sun, 1st January 1820

This tedium led to opportunity. On 3rd September 1833, a 23 year old named Benjamin Day published the first issue of the New York Sun. The paper promised to provide the common man with all the news of the day, while also taking the unprecedented step to fill the pages with adverts. He would sell the paper for a penny and fill it with lurid and captivating tales of horrific suicides and murders, tales of strange violence and uplifting romance. Though a loss maker, Day would sell the advertising spots to companies, providing the first regular and unfettered access for advertisers to the minds (and cash) of previously hard to reach members of society.

Day’s plan was a success. Within 3 months, the advertising revenue started to make a profit. In a year, it had a circulation of 5000 readers, a significant threat to the established press and an irresistible cash cow for likeminded peddlers of sensationalism. Within 2 years, new members of the penny press had sprung up, some focussing on a specific niche such as spots coverage or stomach churning accounts of morgue visits. This competition began a race to the bottom, with the different papers coming up with more and more outrageous stories to try and capture and steal more readers. Journalistic rigour was quickly abandoned along with any semblance of fact or truth. In a famous 1835 issue, the New York Sun reported the findings of a civilisation of promiscuous bat-like creatures who lived on the moon. Despite it’s ridiculousness, the story was a wild success and had a massive impact on the paper’s circulation. The success of the Penny press proved how capturing human attention could make a lot of money. The first attention merchant, according to Wu, had been born.

The capture of attention had begun in a place where people devoted their time to a specific activity. But why stop there? Soon the race to capture people unawares would begin in earnest.

“The Great Wave of Parisian Posters”

Woodblock printing is famously associated with Japan and most people will know some of its iconic art, such as The Great Wave off Kanagawa. What fewer people know is that in the 1800s, Japanese artists pioneered the first use of colour prints and pictures as advertisements instead of the graffiti seen in ancient Greece and Rome or block lettering that was starting to appear in the West.

The detail and eye catching colour is reminiscent of the fashion magazines of today, with elegant figures, finely dressed, perusing the streets and shops. These pieces represent the first documented effort to encourage patronage through illustrated advertisements.

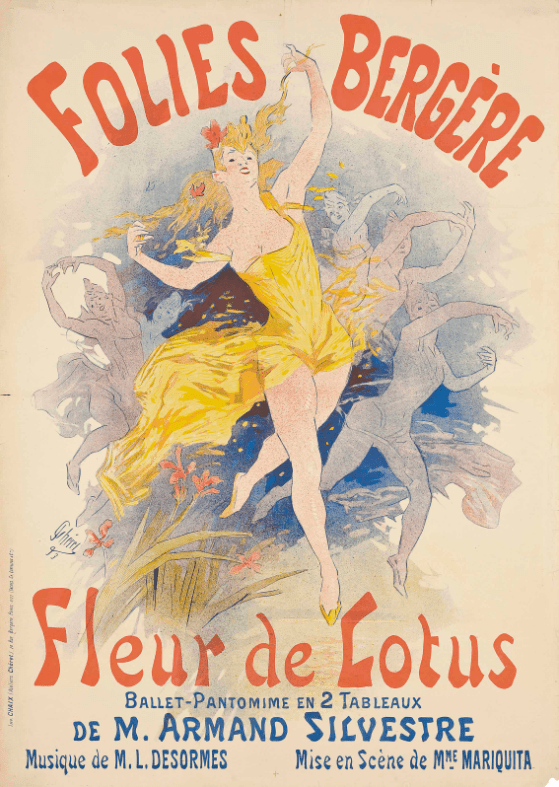

Soon a French artist, Jules Cheret (b. 1836 – d. 1932), would build on this inspiration, along with a new technique of painting oil on limestone, known as lithography, and combine them with some of the baser instincts of humanity. With this combination, his legacy would improve the profits of thousands of products by capitalising on human distractability.

Cheret’s posters were captivating, using colour and the sense of motion to create huge, dynamic posters of to promote different products and companies. The posters also started a well-worn path of capturing attention when it was wandering, while waiting for a friend or an appointment, or even stealing attention when people were trying to focus on something else (perhaps a particularly thrilling newspaper article about the forest of Dartmoor).

While initially described as brilliant and as an eye based education, as with the penny press, copycats soon sprung up, generating a garish race to the bottom and eventually covering the Parisian skyline with base attention triggers – colour, motion, monsters and sexualised muses all had their introduction in the Parisian streets. Paris was defined as a wall of posters, from sidewalk to chimney stack – something that was soon noticed and then cursed by its residents.

These techniques would be refined over the years in an attempt to saturate and compel our limited attention and turn it into profit. These days, the humble poster has been up-scaled into sprawling strings of billboards along road sides, designed to catch people gazing out of the window as passengers or while on autopilot driving from A to B. With the progression of technology, posters would become digitised with even more captivating techniques like flashing lights and pictures that actually move.

Patent medicine:

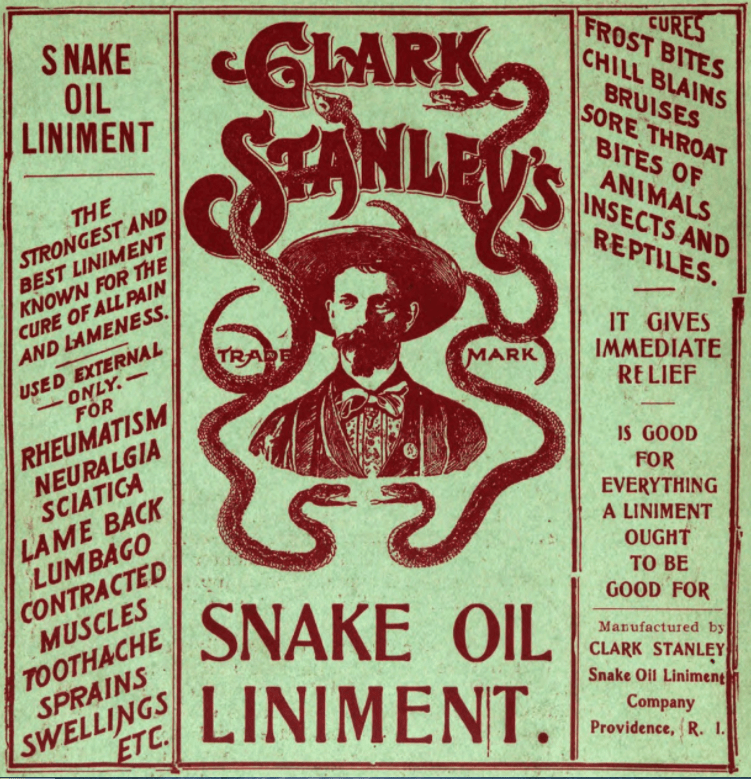

Cowboys are not often sought after for medical advice, but the idea of a secret quick fix has overcome even the most cynical. In 1893, moushtacheoed bandana wearer, Clark Stanley (b. 1854 – d. c 1916) was offering an elixir that would cure all ills. His snake oil liniment, he claimed, would cure rheumatism, neuralgia, sciatica, lame back, lumbago, contracted muscles, toothaches, sprains, swelling and much more.

These types of elixirs were known as patent medicines. They would take many forms, almost always advertised by an alluring character (Cowboy Clark Stanley for example) and feature some form of secret ingredient. In an age of limited entertainment, Stanley would take his caravan across the USA and put on shows. These were extravagant productions where Stanley would take a live rattlesnake and squeeze the life from it in front of a captivated crowd. He’d throw the dead snake into a mysterious steaming broth where it would simmer. Soon an oily meniscus would form which Stanley would skim off the top and pour into a bottle and sell for a tidy profit to the enraptured people who stood before him.

The patent medicine men would pioneer the hard sell – the art of telling customers that a product will cure their wildest dreams regardless of the truth of the matter. They would also be the first to generate profits from direct mail or spam campaign techniques, sending millions of pamphlets through people’s doors, many of whom would spend 91 cents on a patent medicine product before realising it was complete garbage.

The legacy of patent medicine would be extreme with many techniques still used today (consider modern cosmetics with their secret ingredients or celebrity endorsements). Plunging into a gloomy future, peppered by advertisements and hard sell of spam, social media, scams and popups it would be easy to think that the ad- saturated world we live in will forever be the norm. The reason why it’s so important to understand the history of each of these attention merchant mediums is to understand what happens next.